The economics of behind-the-meter battery storage. Part 1: Reducing your energy bill

What are behind-the-meter commercial & industrial (C&I) batteries?

We’re talking about smaller batteries, typically 100kWh to 5MWh in size, installed at a business. Importantly for the business case, the battery co-exists alongside the existing energy load as well as any other energy assets that might also be installed, such as rooftop solar, heat pumps or EV charging. The business is likely connected to the electricity distribution network at the low to medium voltage level.

That’s distinct from “front-of-meter” utility-scale batteries, often large standalone assets or co-located with equally large solar or wind farms and connected to the very-high-voltage transmission network, or very small residential storage in the 5kWh to 15kWh range that you might install in your home.

Why the focus on C&I batteries

Battery storage has been a hot topic in energy markets for a few years now but despite much froth and chatter, in regions like the UK, Europe and Australia the action has generally been restricted to large, utility-scale projects and small residential batteries to increase self-consumption of roof-top solar. There have been relatively few batteries installed by businesses. Why is that? Two main reasons.

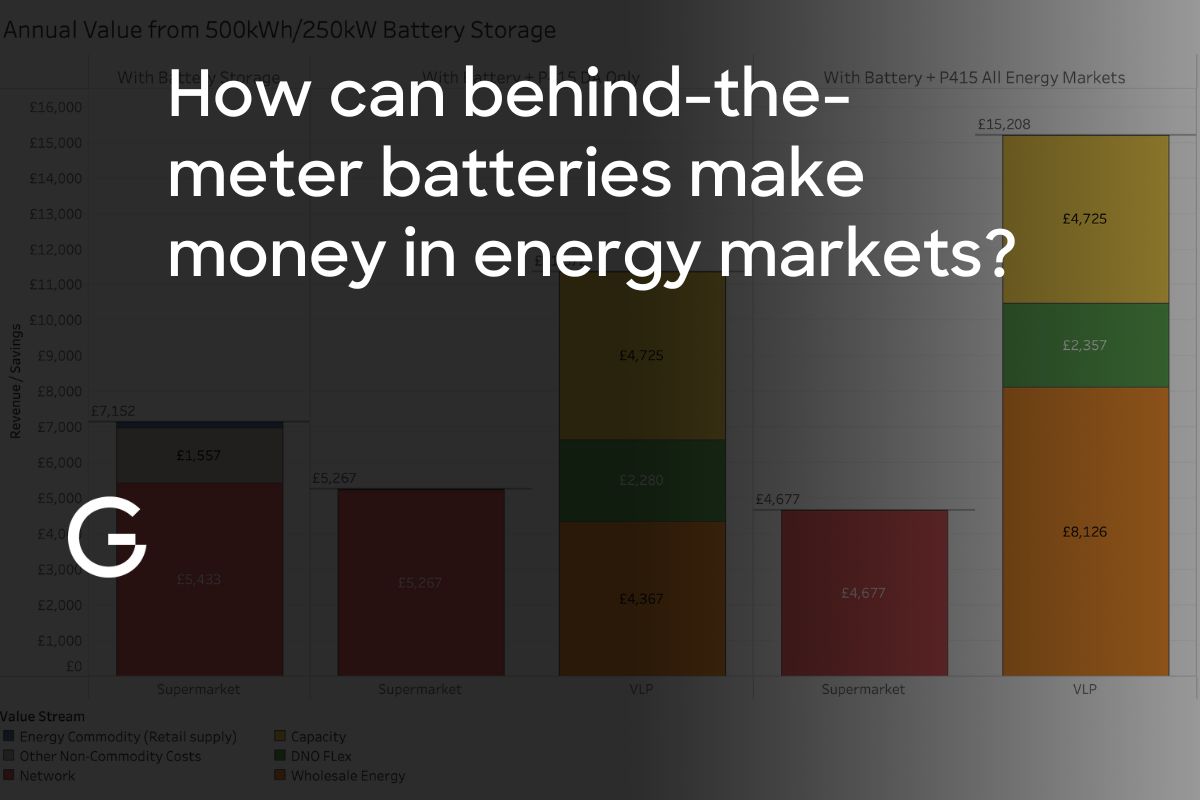

Firstly, those utility-scale projects have access to a range of often lucrative market-based value streams - capacity market revenue, wholesale arbitrage, ancillary services and so on.

Secondly, because economies of scale mean the larger batteries can be built more cheaply. Not that they’re cheap by any means, just that it’s a good deal cheaper on a per kilowatt hour basis to build a 100MWh battery in a field than a 100kWh battery out the back of, say, a supermarket.

Well, that is starting to change driven by a couple of factors: Batteries are (finally) starting to come down in price for the smaller end of the market after remaining stubbornly high for the last couple of years - we’ve seen prices fall by about 40% in the last 12 months - and energy markets are increasingly allowing these smaller batteries to earn revenue from market-based value streams. See this video of P415 in the UK market.

That means they can potentially stack a number of elements of value together to produce a viable investment.

In this two-part post we’re looking at the commercial rationale for installing battery storage at a business premises in the UK, although the economics are similar for many other markets, including Australia and Europe.

How behind-the-meter batteries can make money

Unlike a generation asset such as rooftop solar that produces electricity that you can consume as an alternative to purchasing it from an energy supplier, batteries don’t generate electricity at all, they just shift it in time and incur losses for the privilege.

It doesn’t sound that flash when you say that out loud, but in a world where electricity costs vary widely during the course of a day, month or year, the ability to store energy at one time (when it’s cheap) and use that stored energy later (when it would otherwise be more expensive) can be very lucrative.

In fact batteries are the veritable Swiss army knife of the energy transition and a behind-the-meter battery can make money in a number of different ways, often stacking different pools of value together. Working out when and how to do this though is not trivial and needs careful modelling and planning.

Simplistically you can group the money-making opportunities for behind-the-meter storage into four categories, which themselves can be further broken down something like this:

- Reducing energy supply costs

- Tariff arbitrage: charging cheap, discharging when prices are high

- Solar (and wind) self-consumption

- Demand charge management

- Reducing capacity market costs where applicable such as in the Australian WEM or PJM in the US.

- Earning revenue from providing market services

- Wholesale or spot market arbitrage

- Frequency, balancing and ancillary services

- Flexibility services to the market in response to high wholesale prices

- Earning capacity market revenue

- Providing network capacity (as an alternative to traditional network infrastructure)

- Enhancing limited grid connections, for example for businesses looking to add additional electrical load as part of a site expansion or installation of EV charging infrastructure.

- Deferring traditional network augmentation, earning revenue by providing ‘flex services’ to the local network distribution business

- Delivering reliability (backup power), so critical loads can continue to run when there is a supply interruption (like a UPS does for a server room or data centre).

The focus of this post will be that first point, reducing a business's energy supply costs. To dig deeper into that we first need to understand how a C&I business, such as a supermarket or factory, pays for the electricity it consumes.

The C&I bill stack

A business’s monthly electricity bill is made up from a collection of different charges that cover the entire value chain associated with delivering electricity to the premises. They cover the energy commodity, network and transmission costs, environmental certificates and other policy costs, market fees and few other bits and pieces.

The chart below shows the approximate breakdown for a C&I business in the UK at the time of writing. For other regions the breakdowns will be weighted differently, for example in Australia the DUoS costs (hot pink in the chart) are typically at least 25% of the bill stack and it’s not uncommon for them to be greater than 50%.

Digging deeper: Bundled vs pass-through and fixed vs volumetric

These charges can either be “bundled” or “unbundled”, also sometimes referred to as “pass-through” and different parts of the contract can be billed in different ways, typically:

- Fixed daily or monthly fees. These relate to the elements of energy supply that don't vary with usage, an example might be the costs of metering but here are plenty of others.

- Unit costs based on the volume of energy consumed, measured in kilowatt hours or kWh

- Unit costs based on the peak rate of consumption, measured in kilowatts or kW (or sometimes kilovolt amps or kVA). These costs are typically designed to recover the development of the transmission and distribution network that moves energy from where it’s generated to where it’s consumed.

With a bundled tariff all the different costs in that chart above are rolled together into a simple tariff that usually includes a fixed daily charge as well as a unit charge per kWh consumed.

That unit charge can be a flat rate across all times of the day and year or it can vary based on time-of-use, for example with higher prices during evening peaks and lower costs early in the very early morning when market supply is plentiful and energy demand is low.

With an unbundled or pass-through tariff the end customer will have visibility of all the sub-elements that make up their supply costs - those different colours in the pie chart. Importantly this visibility provides a more nuanced price signal for a business to reduce its supply costs. This can be very valuable for sites with the ability to flex their usage.

Reducing operational costs

Now we’re going to step through some worked examples of how a behind-the-meter C&I battery might create value based on three of the most common use-cases:

- Energy arbitrage: charging cheap, discharging when prices are high

- Solar (and wind) self-consumption

- Demand charge management

Each use-case is illustrated using some current examples of tariffs that would apply to business in the UK. Our example site for this exercise is a small supermarket in Maidstone, Kent that consumes 470MWh per year. Its average daily consumption looks like this:

Tariff arbitrage: charging cheap, discharging when prices are high

This is the most basic use-case for anyone looking at behind-the-meter storage and is often at the foundation of any battery storage business case, including for the largest utility scale projects.

The idea is simply for the battery to charge at an off-peak rate, perhaps overnight, and discharge into the site load during peak times, perhaps in the afternoon. For that to be profitable then the difference between the peak and off-peak rates in the tariff - often returned to as the “daily spread” - needs to be greater than the Levilised Cost of Storage or LCoS. The LCoS is the lifetime cost of the battery divided by the lifetime quantity of energy it can cycle and is a useful metric for working out if a battery project is likely to be profitable.

The graphic below shows current pricing for Octopus’s Shape Shifter tariff to illustrate what kind of daily spread is possible in today’s market in the UK for a site like our Maidstone supermarket.

To illustrate things further we’ve included the average load profile of our site in dark blue and then how that profile might look with the addition of a battery that’s configured to target the difference in the tariff rates.

In this case the tariff provides a very healthy spread of about 26p/kWh. Is that enough for a battery investment? Well if we compare that spread to the LCoS for a C&I battery of about 16p/kWh then yes, it looks pretty good. We won’t go into detail on LCoS here but for those breaking out their calculators this is based on a battery capex of £350 per kWh.

Solar (and wind) self-consumption

It’s very common for a behind-the-meter battery to be installed alongside some renewable energy generation, most commonly rooftop solar but in some markets that can also include wind.

By adding an asset like rooftop solar to a site and allowing the battery to charge from that solar you can effectively increase the daily spread that the battery has access to. Rather than charging at the cheapest rate from the supply contract the battery can now charge from excess solar.

It’s important to point out that our solar energy is certainly not free, someone has to pay for that system to be installed, but typically the Levilised Cost of Energy (LCoE) from rooftop solar will be cheaper than grid-supplied energy. Another equally important point is this approach only really works if there is excess generation from that solar or wind that would otherwise go to waste.

If the significant majority of the energy generated from solar is already being consumed by the site load then adding a battery is probably a bad idea unless there are other jobs for that battery to do. We need some spare solar to make this work. Equally, if any excess generation is already receiving a feed-in-tariff then again adding a battery will likely not make sense as the price spread is reduced.

The graphic below shows how rooftop solar coupled with a flat energy supply tariff can create a price spread for a battery that doesn’t exist absent of some onsite generation.

In this case our supermarket has installed an oversized solar system that’s generating significant excess electricity. Note the blue energy consumption plotted on the right-hand axis goes negative in the middle of the day illustration export back to grid.

The battery can charge off this excess and discharge into the site load after dark. For this illustration we’ve assumed a LCoE from the solar of 10p/kWh which is reasonable for our site in Maidstone. LCoE varies based on the cost of installing the solar system and the yield that system will provide, which is a product of tilt, orientation and local weather conditions.

The combination of flat tariff plus excess solar provides a price spread of 14p/kWh. If we compare this back to our LCoS at 16p/kWh then we’re not in the money. For this battery to make sense the site needs a bigger price spread which it might achieve by switching tariffs.

Demand charge management

For the next value stream the business will need to be on an unbundled or pass-through tariff. For these customers they’ll often see an itemised cost based on the peak rate that they consumed energy over the billing cycle, this will be in kW or kVA. This cost, commonly referred to as a demand charge, is typically levied by the distribution network owner that the site is connected to.

A battery can work to reduce these demand charges by “squashing” peaky periods of energy use. The theory is simple enough and is illustrated in the graphic below where the battery is able to reduce the “billable demand” on this day from 100kW down to 80kW.

In practice these charges can include a bewildering array of rules for when they apply and how they’re calculated. It’s very important that the battery control system - the brain of the battery - understands these rules, as well as being able to accurately forecast site demand, if it’s to effectively reduce demand charges. For more on network tariffs check out this Thinking Energy edition

Typically demand charge management won’t make commercial sense by itself but should be considered alongside the other value streams discussed earlier and those that will be covered in the next post covering market services. There are a few rare exceptions to this but those normally only crop up for sites connected to very thin, expensive networks where demand costs are truly eye watering - Ergon in Queensland, Australia anyone?

Bringing it all together

For a behind-the-meter battery investment to be commercially viable it will often require more than one value stream to be targeted - there's often just not enough value in a single element - and the projects delivering the best financial returns will be stacking market revenue in addition to reduce energy supply costs. More on that in Part 2 though.

The graphic below shows what combining the three approaches discussed above might look like for our supermarket, with the battery charging overnight during off-peak tariff rates in order to have a sufficient state-of-charge to squash that early morning demand peak, and then charging again from excess rooftop solar in the middle of the day to target that very expensive peak rate in the evening.

This is of course highly stylised and in real life there is plenty of additional complexity to work out whether a battery is a good investment and the best way to operate it.

The wrap

The economics of behind-the-meter battery storage for C&I customers in the UK, and other markets around the world, are evolving rapidly. This has been driven by falling battery costs, increasing market volatility driving price spreads in tariffs and improved access to market services.

From tariff arbitrage to enhancing solar self-consumption and managing demand charges, these batteries offer businesses an opportunity to reduce operational costs and build a more resilient energy strategy. However, achieving a positive return on investment requires careful consideration and is highly sensitive to site-specific factors such as energy tariffs, load profiles, grid connections and available renewable energy generation.

In Part 2 of this series, we’ll dive into the revenue-generating opportunities available to behind-the-meter battery storage systems that can access the wholesale energy market. From providing ancillary services and flexibility to supporting capacity markets, we’ll explore how businesses can tap into broader market-based revenue streams.

By stacking these opportunities alongside cost-saving measures, C&I customers can position themselves to not only reduce their energy bills but also participate actively in the energy transition. Stay tuned!

.png)